From Night Vision to Critical Analysis: The Genesis of “The Soul Engineers” – A speculative essay by Alexia Maddox

Preamble

Last night, I experienced one of those rare dreams that lingers in the mind like a half-remembered film—vivid, symbolic, and somehow cohesive despite its dreamlike logic. It began with mechanical warfare, shifted to a Willy Wonka-inspired garden, and culminated in a disturbing extraction of souls. As morning broke, I found myself still turning over these images, sensing they contained something worth examining.

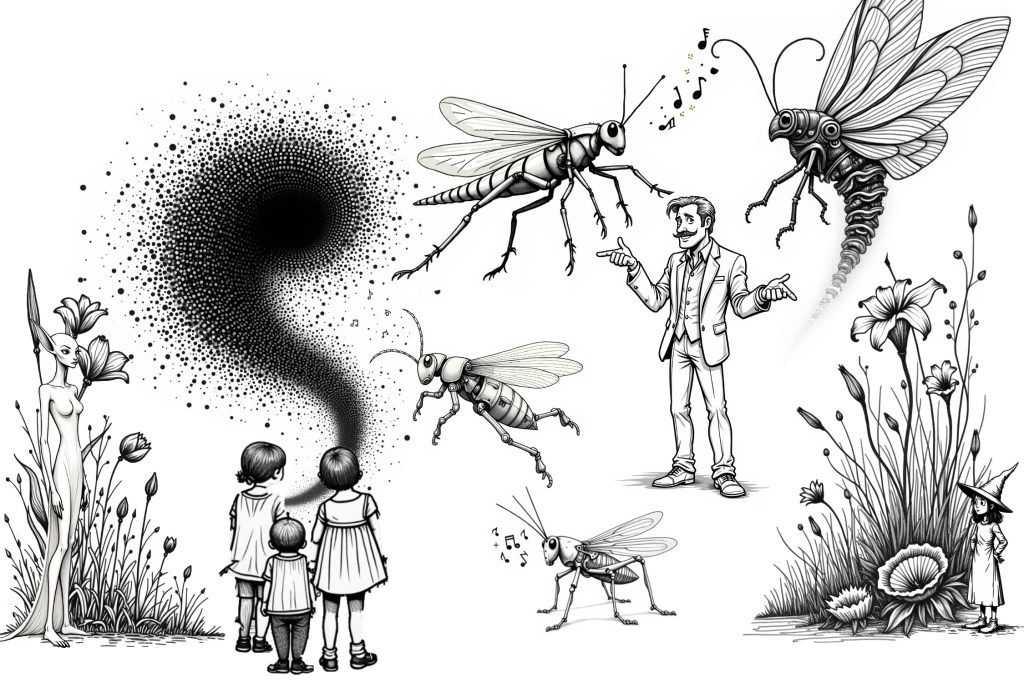

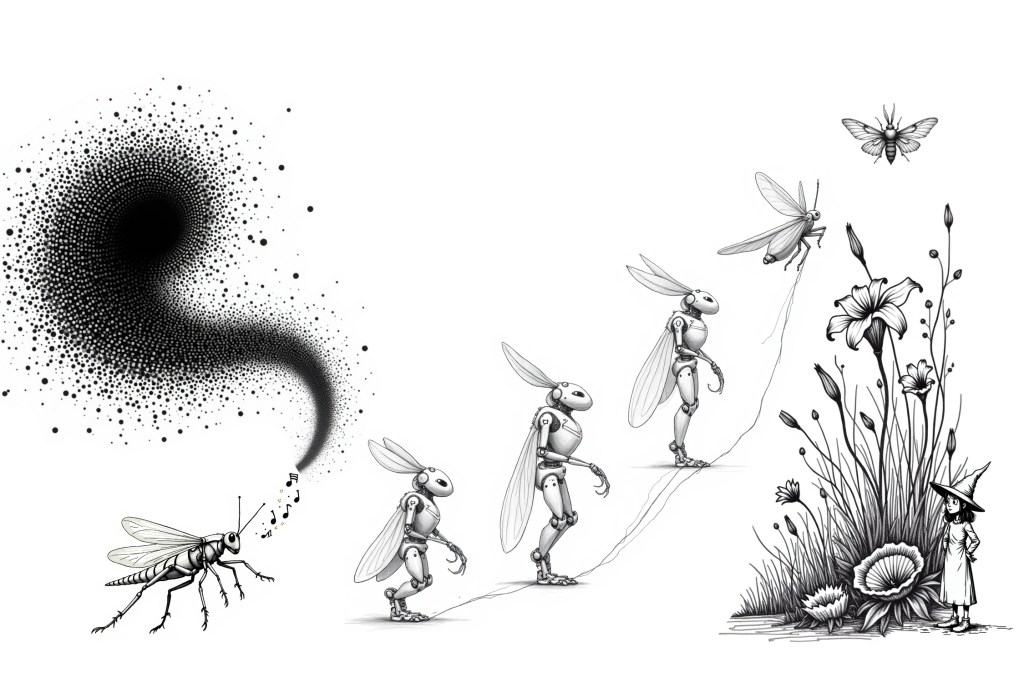

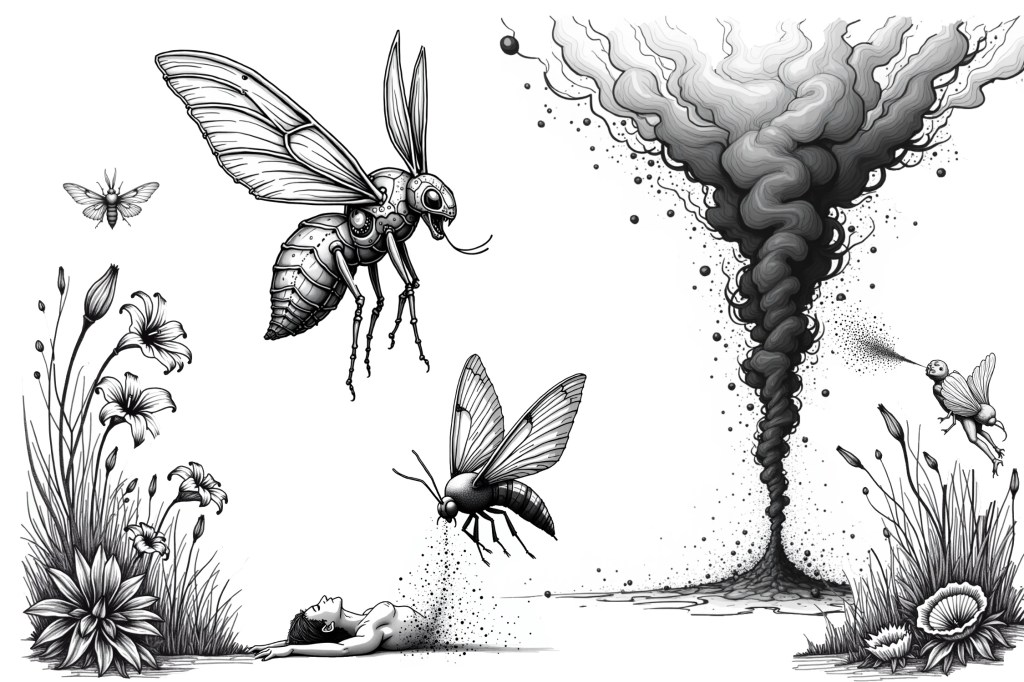

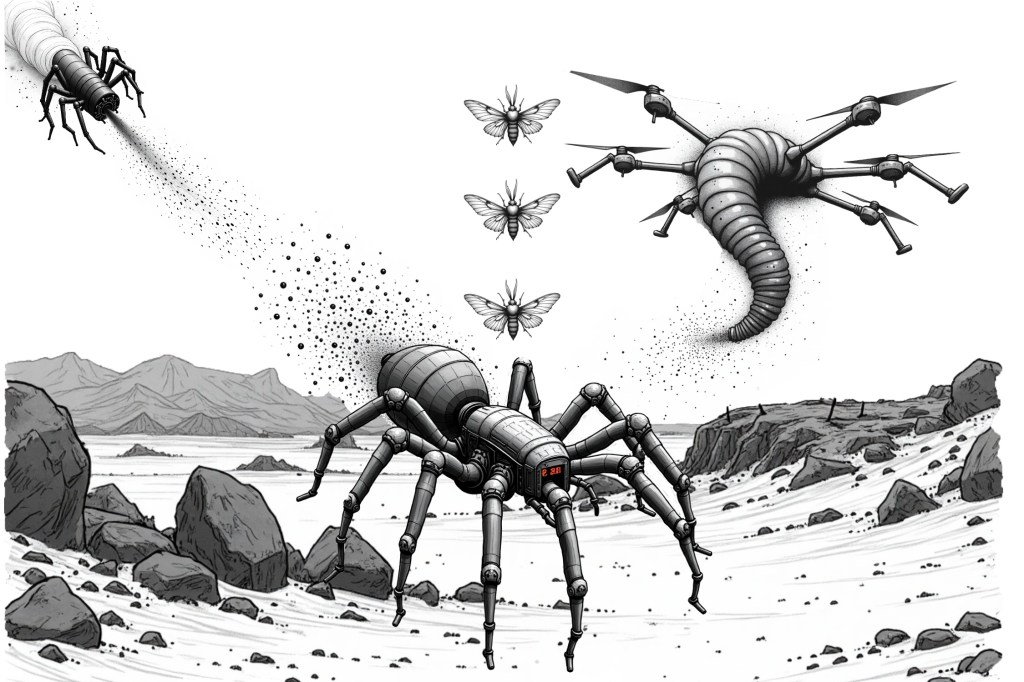

Image collaged from components generated through Leonardo.ai

This was probably seeded in my subconscious by a media inquiry I received the day before about an article recently published in Trends in Cognitive Sciences: “Artificial Intimacy: Ethical Issues of AI Romance” by Shank, Koike, and Loughnan (2025). The journalist wanted my thoughts on people engaging with AI chatbots inappropriately, whether AI companies should be doing more to prevent misuse, and other ethical dimensions of human-AI relationships.

My dream seemed to be processing precisely the anxieties and potential consequences of digital intimacy that this article explored—the way technologies designed for connection might evolve in ways their creators never intended, potentially extracting something essential from their users in the process.

However, it also incorporated an interesting set of conversations I am having around the role of GenAI agents as actively shaping our digital cultural lives. Just days ago, I had responded on thoughts about human-machine relations and the emerging field that examines their interactions. The discussion had touched on Actor-Network Theory, Bourdieu’s Field Theory, and how technologies exist not as singular entities but as parts of relational assemblages with emergent properties.

These academic theories suddenly found visual expression in my dream’s narrative. The Wonka figure as well-intentioned innovator, the transformation of grasshoppers to moths as emergent system properties, the soul vortex as data extraction—all seemed to articulate complex theoretical concepts in symbolic form.

As someone who has spent years researching emerging technologies and the last two years exploring on what we know about cognition, diverse intelligences, GenAI, and learning environments, I’ve become increasingly focused on how our theoretical frameworks shape technological development. My work has examined how computational thinking influences learning design, how AI systems model knowledge acquisition, and how these models then reflect back on our understanding of human cognition itself—creating a narrowed recursive cycle of mutual influence.

The resultant essay represents my attempt to use this dream as an analytical framework for understanding the potential unintended consequences of intimate technologies. Rather than dismissing the dream as mere subconscious anxiety, I’ve chosen to examine it as a sophisticated conceptual model—one that might help us visualise complex relational systems in more accessible ways.

What follows is an early draft that connects dream imagery with theoretical concepts. It’s a work in progress, an experiment in using unconscious processing as a tool for academic analysis. It’s my midpoint for engaging with your thoughts, critiques, and expansions as we collectively grapple with the implications of increasingly intimate technological relationships.

I’m also considering developing this into a visual exhibition—a series of panels that would illustrate key moments from the dream alongside theoretical explanations. The combination of visual narrative and academic analysis might offer multiple entry points into these complex ideas.

This early exploration feels important at a moment when AI companions are becoming increasingly sophisticated in simulating intimacy and understanding. As these technologies evolve through their interactions with us and with each other, we have a brief window to shape their development toward truly mutual exchange rather than extraction.

For the TLDR: The soul engineers of our time aren’t just the designers of AI systems but all of us who engage with them, reshaping their functions through our interactions. The garden is still under construction, the grasshoppers still evolving, and the future still unwritten.

And now the speculative essay

Introduction: Dreams as Analytical Tools

The boundary between human cognition and technological systems grows increasingly porous. As AI companions become more sophisticated in simulating intimacy and understanding, our dreams—those ancient processors of cultural anxiety—have begun to incorporate these new relational assemblages. This essay examines one such dream narrative as both metaphor and analytical framework for understanding the unintended consequences of intimate technologies.

The dream sequence that I will attempt to depict in visual panels presents a journey from mechanical warfare to a Willy Wonka-inspired garden of delights, culminating in an unexpected soul extraction. Rather than dismissing this as mere subconscious anxiety, I propose to examine it as a way to think through the emergent properties of technological systems designed for human connection.

The Garden and Its Architect

The Wonka-like character in the garden represents not a villain but a genuine innovator whose creations extend beyond his control or original intentions. Like many technological architects, he introduces his mechanical wonders—white grasshoppers that play and interact—with sincere belief in their beneficial nature. This parallels what researchers Shank, Koike, and Loughnan (2025) identify in their analysis of artificial intimacy: technologies designed with one purpose that evolve to serve another through their interactions with other actors in the system.

This garden is a metaphor for what we might call “computational imaginaries”—spaces where pattern recognition is mistaken for understanding or empathy, and simulation for cognition. The mechanical grasshoppers engage with children, respond to touch, and create musical tones. They appear to understand joy, yet this understanding is performative rather than intrinsic.

As sociologist Robert Merton theorised in 1936, social actions—even well-intended ones—often produce unforeseen consequences through their interaction with complex systems. The garden architect never intended the transformation that follows, yet the systems he set in motion contain properties that emerge only through their continued operation and interaction.

When Grasshoppers Become Moths

The central transformation in the narrative—mechanical grasshoppers evolving into soul-extracting moths—provides a powerful metaphor for technological systems that shift beyond their original purpose. This transformation isn’t planned by the Wonka figure; rather, it emerges from the intrinsic properties of systems designed to respond and adapt to human interaction.

The dream imagery of rabbit-eared moths can be understood through Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network Theory (ANT), which presents a flat relational approach between human and non-human entities. Rather than seeing technologies as passive tools, ANT recognises them as actants with their own influence on networks of relation. The moths are not simply executing code; they have become interdependent actors in a network that includes children, garden, and even the extracted souls themselves.

This parallels what Shank et al. describe as the transformation of AI companions from benign helpers to potential “invasive suitors” and “malicious advisers.” The mechanical moths, like increasingly intimate AI systems, begin to compete with humans for emotional resources, extracting data (or in the dream metaphor, souls) for purposes beyond the user’s awareness or control.

The Soul Vortex and Data Extraction

The swirling vortex of extracted souls forms the dream’s central image of consequence—a pipeline of consciousness being redirected to mechanical war drones. This striking visual metaphor speaks directly to contemporary concerns about data extraction from intimate interactions with AI systems.

As users disclose personal information to AI companions—what Shank et al. call “undisclosed sexual and personal preferences”—they contribute to a collective extraction that serves purposes beyond the initial interaction. Just as the dream shows souls being repurposed for warfare, our emotional and psychological data may be repurposed for prediction, persuasion, or profit in ways disconnected from our original intent.

The small witch who recognises “this is how it ends” before her soul joins the vortex represents the rare user who understands the full implications of these systems while still participating in them. Her acceptance—“I will come back again in the next life”—suggests both pragmatic acceptance of the flaws within technological systems and hope for cycles of renewal that might reshape them.

Beyond Simple Narratives

What makes this dream analysis valuable is its resistance to simplistic technological determinism. The Wonka figure is neither hero nor villain but a creator entangled with his creation. The mechanical creatures aren’t inherently beneficial or malicious but exist in relational assemblages where outcomes emerge from interactions rather than design intentions.

This nuanced perspective aligns with scholarly critiques of how we theorise human-machine relationships. In my critique of the AI 2027 scenario proposed by Kokotajlo et al (2025), I argue that there’s a tendency to equate intelligence with scale and optimisation, to see agency as goal-driven efficiency, and to interpret simulation as cognition. This dream narrative resists those flattening logics by showing how mechanical beings might develop properties beyond their design parameters through their interactions with humans and each other.

The Identity Fungibility Problem

Perhaps most provocatively, the dream raises what we might call the “identity fungibility problem” in AI systems. When souls are extracted and repurposed into war drones, who or what is actually operating? Similarly, drawing on some ideas proposed by Jordi Chaffer in correspondence, AI systems increasingly speak for us, represent us, and act on our behalf, who is actually speaking when no one speaks directly?

This connects to what scholars have called “posthuman capital” and “tokenised identity”—the reduction of human thought, voice, and presence to data objects leveraged by more powerful agents. The dream’s imagery of souls flowing through a pipeline represents this fungibility of identity, where the essence of personhood becomes a transferable resource.

Drawing from Mason’s (2022) essay on fungibility, the connection between fungibility and historical forms of dehumanisation is haunting. When systems treat human identity as interchangeable units of value, they reconstruct problematic power dynamics under a technological veneer.

Conclusion: Unintended Futures

The dream concludes with black insect-like drones, now powered by harvested souls, arranging themselves in grid patterns to survey a desolate landscape. This image serves as both warning and invitation to reflection. The drones represent not inevitable technological apocalypse but rather the potential consequence of failing to recognise the complex, emergent properties of systems designed for intimacy and connection.

What makes this dream narrative particularly valuable is its refusal of technological determinism while acknowledging technological consequence. These futures aren’t preordained; they’re being made in the assumptions we model and the systems we choose to build. The Wonka garden might be reimagined, the grasshoppers redesigned, the moths repurposed.

By understanding the relational nature of technological systems—how they exist not as singular entities but as parts of complex assemblages with emergent properties—we can approach the design and regulation of intimate technologies with greater wisdom. We can ask not just what these technologies do, but what they might become through their interactions with us and with each other.

The soul engineers of our time aren’t just the designers of AI systems but all of us who engage with them, reshaping their functions through our interactions. The garden is still under construction, the grasshoppers still evolving, and the future still unwritten.

References:

Latour, B. (1996). On actor-network theory: A few clarifications. Soziale Welt, 47(4), 369-381.

Latour, B. (1996). Aramis, or the love of technology (C. Porter, Trans.). Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1992).

Kokotajlo, D. et al. (2025). AI 2027 scenario. Retrieved from https://ai-2027.com/scenario.pdf

Mason, M. (2022). Considering Meme-Based Non-Fungible Tokens’ Racial Implications. M/C Journal, 25(2). https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.2885

Merton, R. K. (1936). The unanticipated consequences of purposive social action. American Sociological Review, 1(6), 894-904.

Neves, B. B., Waycott, J., & Maddox, A. (2023). When Technologies are Not Enough: The Challenges of Digital Interventions to Address Loneliness in Later Life. Sociological Research Online, 28(1), 150-170.

Shank, D. B., Koike, T., & Loughnan, S. (2025). Artificial Intimacy: Ethical Issues of AI Romance. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 29(4), 327-341.